This is actually about my collection of odd t-shirts, but it’s also about mid-20th-century science fiction and global politics. Bear with me…

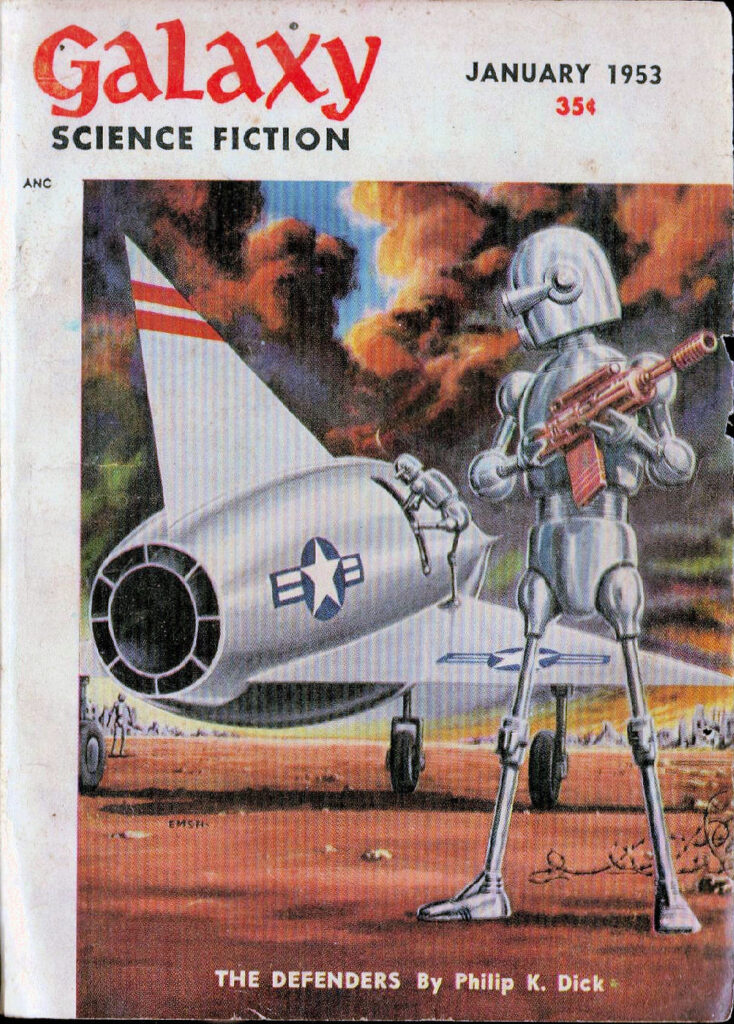

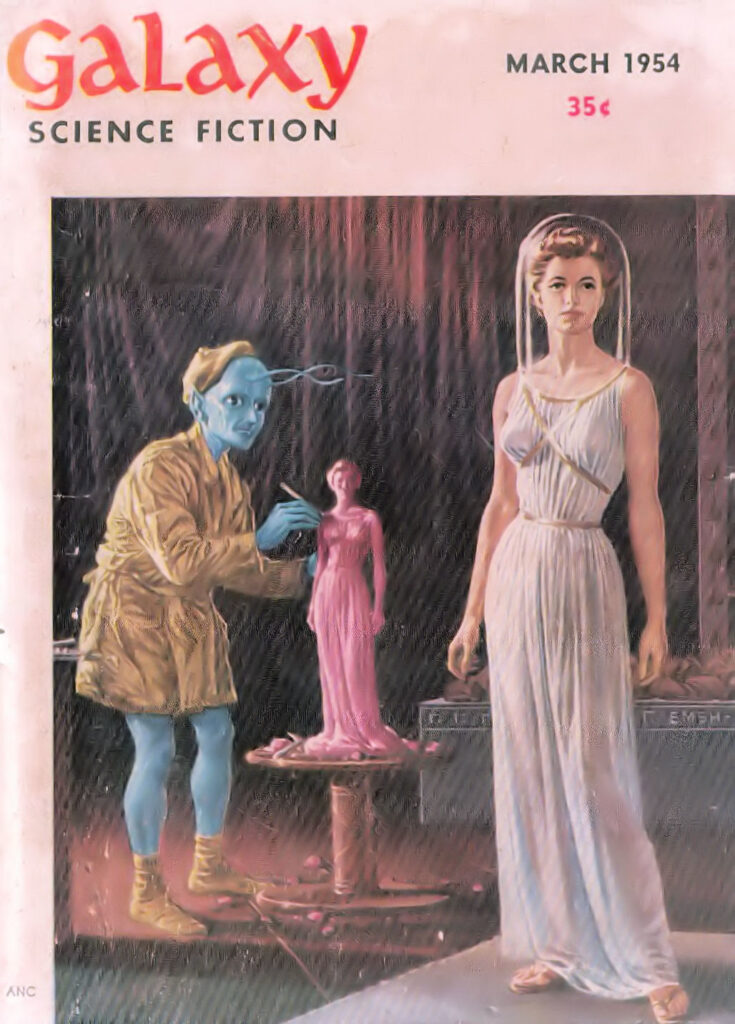

When I was young I read a lot of science fiction. I was into escape, and in those days we didn’t have PlayStation or Xbox or Switch. So I hit the public library and devoured great gobs of space opera that first saw the light of day in pulp magazines with names like Galaxy, Astounding, Fantastic Universe, Startling Stories, Amazing Stories, and Worlds of If.

Sci fi from the ’50s and early ’60s was heavy on starships and galactic empires and heroic human beings colonizing far planets for the greater glory of… something. Mainly I loved it, but the “something” was never quite clear to my ten-year-old mind.

Though it had to be a pretty powerful motivator, whatever it was, to get a couple of hundred people to jam themselves inside a metal tube and travel light-years to a planet with green skies and giant intelligent leeches to build a factory for processing giant purple wahoonies (like oranges, only igloo-sized) into useful anti-depressants for the folks back home. Or bring along the wives and kids, too, and carve their own wahoonie plantations out of the alien earth.

No doubt those jut-jawed heroes of pulp sci-fi had their reasons for conquering the stars. They just didn’t state them straight out; it was all supposed to be self-evident.

But thinking back, I see that a lot of those stories were all about the human race’s manifest destiny to spread out and humanicate the universe. The United States had pushed forward across North America from one coast to the other; why stop there? Why ever stop?

Some authors helpfully gave humanity an excuse to conquer: as if humanity didn’t really want to rule the galaxy, but was forced to take up the starship and blaster rifle by circumstance alone.

Sometimes the motivator was population pressure; as if humans would create a world government and learn to travel at 10,000 times the speed of light and yet fail to develop good birth control. (Robert Silverberg, Master of Life and Death, Ace D-237, 1957).

And then there were the stories in which the human race was forced to defend itself against the Giant Space Wedgies who had tried (but failed) to conquer Earth. So humanity had no choice other than to wage titanic space battles and conquer all the WedgieWorlds to make Earth, and the galaxy, safe for all time. And incidentally end up running a galactic empire filled with grateful subject races.

Very, very occasionally some old lefty-turned-hack-writer would work the greed angle into his tale of star conquest. As if the human race would conquer the universe for any but altruistic reasons! A lot of sci-fi editors wouldn’t risk such subversive thought.

Because in the typical 1950s galactic empire, humans were mainly good; scaly reptilians with three arms were bad if they were trying to settle the same planets we were, but good if they were primitive peoples who freely welcomed the benevolent guidance of human civilization.

And worked cheap. Oh sure, you could use robots for labor, but that was asking for trouble (unless you were Isaac Asimov). Robots were always either not smart enough, or much too smart; and either way, they knew how to pick the lock on the gun rack.

But eventually the whole galaxy would be settled and Earth-like and Moms and Dads and their 3.2 kids would live an ideal suburban lifestyle on planets from here to the galactic core. And off in the distance, there would be a cadre of heroic space explorers ever pushing the boundaries of human civilization out farther… and farther.

It was all good to ten-year-old me. I’d probably still get a kick out of the old space operas today. Because aside from the cultural propaganda they pushed, they were colorful, wacky, pulp adventures.

What’s not cool about being first officer on a tramp starship, descending from orbit to a desert world of ancient cities and secrets and wily old potentates with tentacles? With supplies for the Earth mining colony and the Space Marines garrison, and perhaps a diplomatic pouch for the consul about the activities of the brown, wrinkly agents of the rival Coprolite Stellar Hegemony? I remember those old stories so well I could write one in my sleep, for better or worse.

Just old pulp fiction, though. Not real. Nothing to get excited about.

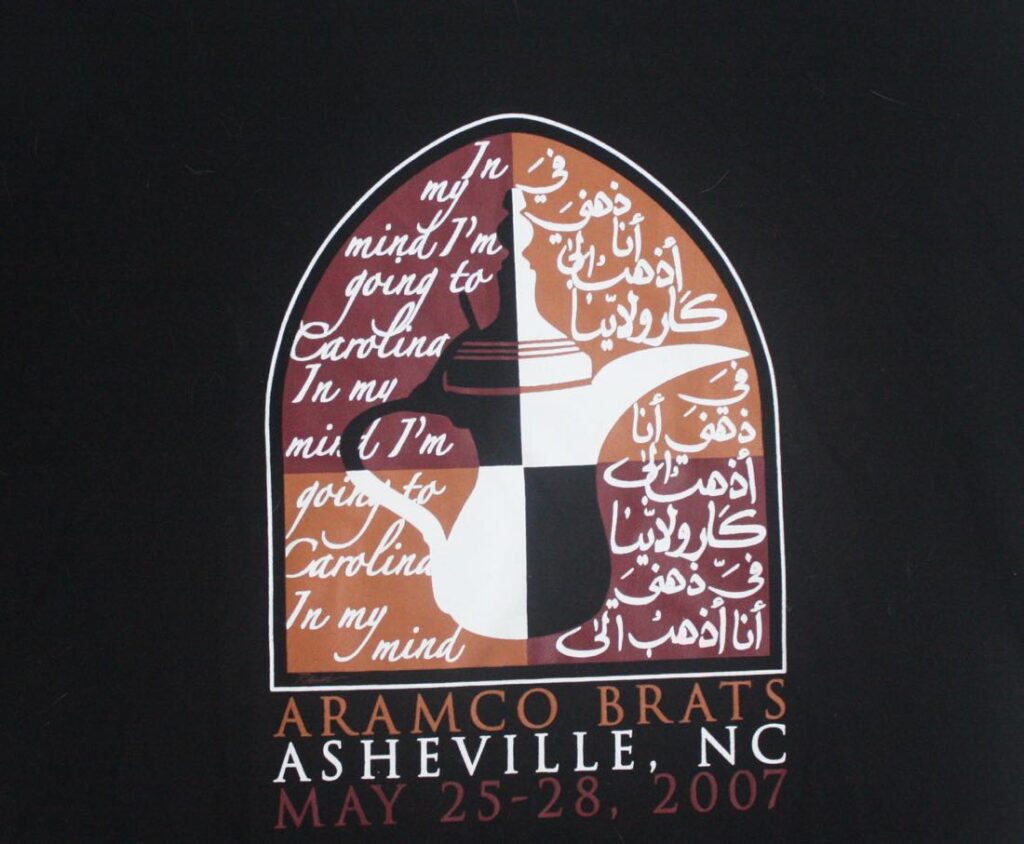

And then I went hunting for odd t-shirts down at the Goodwill and found an actual t-shirt from the Galactic Empire. It really existed. Here’s the design from the shirt:

You might ask: what the hell is an Aramco brat? Why did they have a convention in Asheville? What’s the joke in the phrase, “In my mind, I’m going to Carolina?” And how is this the Galactic Empire?

Well…

After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire 100 years ago, the great powers of the world sat down together, opened a bottle of whiskey, and divvied up the defunct empire’s territories from Egypt all the way to Iraq.

America wasn’t a great power yet — just pretty good. But Standard Oil of California (later, Chevron) made its own move in the Mideast: in 1933 it inked a deal with the king of the newly unified Saudi Arabia to find and exploit petroleum deposits in the Arabian peninsula. Signing that deal was probably the first thing the new Saudi government ever did.

Saudi Arabia had a few million people, Mecca, a lot of wildly hostile desert, and a pretty good idea of how to live in it. But no oil exploration expertise. So Standard brought its own men — and their families — from America. Over time it formed partnerships with other companies that eventually became the Arabian American Oil Company, or Aramco.

Aramco was its own little country, almost its own little world. It completely controlled Saudi Arabian oil production. It had its own foreign policy, separate from America’s: pro-Saudi Arabia, anti-Israel. The U.S. federal government signed off on this, even gave the Company a secret tax break to make up for the 50 percent that King Ibn Saud skimmed off the profits.

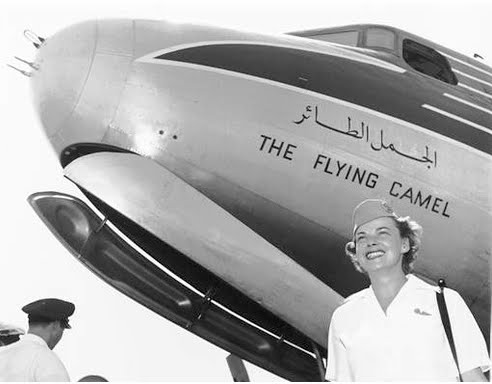

And so Aramco built colonies in Saudi Arabia: self-contained replicas of American suburbia floating in the desert like so many space stations. The American oil men who ran the business committed to the Company for the long haul, and almost always brought their families with them. On one of the Company’s airliners, which made regular transatlantic flights from New York: the Flying Camel, the Flying Gazelle, the Flying Oryx.

Dhahran, one or two others: thousands of white or light-brown Americans lived inside the fences of these places at any given time.

Outside the compound: camels, Bedouins, Islam, desert, wild dogs, Arabia. Inside the compound: lawns, trees, bowling, swimming pools, American-style schools, first-run movies, Boy Scouts, and booze. An idyllic Leave-it-to-Beaver-Land. Pictures and memoirs can be found on the Internet, with a little digging. In a quiet way, they boggle the mind.

Mind you the early days in the Aramco compounds were pretty wild and wooly, when everyone lived in prefab housing and there wasn’t much of a fence; wild donkeys would wander the streets and the kids would catch them and ride them to school.

Even the adults might play wild donkey polo or snare gazelles and keep them as pets. And giant Company construction vehicles might roar down any street at any time, so you’d better not leave your bicycle lying out there.

But there were Indian and Arab servants in every household: Mom never cooked, the kids never shined their own shoes or did chores, and Dad didn’t even have to mow the lawn unless he enjoyed it.

The red Company cars would take Dad out to the Company golf course for eighteen holes with his friends and the Bedouin caddies. The fairways were sand and the greens were asphalt, and camels could block a shot at any moment. But the Company was bent on recreating America in the desert, dammit, and the little details weren’t important.

If you were a kid, an Aramco Brat, a boy or girl suddenly pulled out of Anytown USA by your parents and flown off to Arabia for years and years in the desert, you were in Hell… and Heaven, simultaneously.

Hell, because you were in the middle of nowhere, in an isolated community surrounded by desert—and desert peoples who didn’t always like you much. And there was murderous heat in the summer, and sand on the wind to get into your eyes and teeth and even your hot dog.

And boredom. Lots and lots of boredom, and nothing but the same faces to see and talk to day after day. And chant to yourself, “In my mind, I’m back in Anytown… In my mind, I’m back in Anytown…”

But Planet Aramco was also heaven, because the Company did its best to make you happy. All the comforts of hometown America, dances and shows, and the giant community swimming pool where everyone gathered after five—all free, or close enough.

Or maybe your dad kept some fine Arabian horseflesh down at the Hobby Farm, the Company horse stables, and you could go tearing off across the land like a twelve-year-old Lawrence of Arabia. Or go whole-hog for the gymkhana and dressage routine, if you were a girl with a thing for horses.

As for toys, the Company’s buyers would gather the finest toys in the world and fill a vast room with them in the massive Dining Hall complex before Christmas, where you and your parents could shop at your leisure. And on Christmas Day, Santa would arrive in Dhahran by helicopter — right on schedule.

And you might hitch a ride to Half Moon Bay, where the desert sand dunes spilled right down into the blood-warm water of the Persian Gulf, and you and your friends could wade out 100 yards from shore on a submerged dune and sit down in a circle with the water only up to your chin. While in the distance, dhows glided across the waters.

You could skin-dive there, too, or at least come down for the gigantor beach parties the Company threw several times a year.

And if that wasn’t enough, you joined the Scouts and went off on expeditions to the desert in Company trucks, or hopped a Company DC-3 with your troop on some longer excursion somewhere ’round the Persian gulf. Or took a launch over to Bahrain just 15 miles offshore in the Gulf, and hang out in an island nation that supported something resembling Western culture, thanks to the Brits.

And a Company plane would fly you and your family off to Beirut for three weeks every other year in a swanky French hotel, and the other year send you all home to the states for 90 days of school-free fun.

And it was all free, or so close to free that it didn’t matter. Because you and your parents were living for basically nothing and piling up cash in the bank, doubly-so because they paid no income tax. On Planet Aramco, the benevolent Company took care of everything.

Just as the massive gravity in the heart of a black hole breaks down the laws of physics, so did the weight of all that oil money break down and suspend the rules of capitalism for those who actually lived on the surface of Planet Aramco.

Our world was science fiction. Or science fiction was our world. We just didn’t know it. Everywhere in the world of the 1950s, little space colonies of American or western civilization and technology descended from the sky to float in alien seas and harvest or control the bounty thereof: Planet Aramco, Planet Bahrain Oil, Planet Occupied Japan, Planet NATO, Planet Bechtel, and on and on.

Taken all together, it was the Galactic Empire of the pulps: after defeating vast enemy empires, human (aka American) civilization spread out across the globe to stabilize and protect—and control and exploit—all the far-flung alien lands of the world. And Americans who went out and lived in that empire, in the 50s, will tell you what a wondrous thing it could be. For them.

But things have changed. The native elites took their share of the wealth, educated themselves, and started running their own industries. The Saudis bought out Aramco in 1980 and (eventually) put in their own management—Saudis can sit in a boardroom as well as Americans do. Across the world, space colony after space colony of American technocrats shut down or changed hands.

In the end the aliens took over the empire, after all. And the Aramco Brats of yore meet in conventions to remember the good old unreal days and renew acquaintance with one another.

Planet Aramco is still there—now called Saudi Aramco, thank you. The Aramco compounds still exist. They are still full of expatriate Saudi Aramco employees, business is still done in English, the schools are still great, and expatriates have rights inside the compound that don’t exist in the rest of Arabia. And everybody still goes down to Half Moon Bay to party, and the golf course is still there, too—now with real grass.

The Saudi Aramco technocrats are Indian and Chinese and European and, yes, Arabian, and even some Americans. But it’s a Saudi show, now. Though you can still find places where all the Americans gather, where it still looks like the good old days, or at least a Rotary Club meeting in Houston.

In slightly-more-permissive Bahrain, for example—now an easy drive over the Red Sea from Planet Aramco via the King Fahd causeway—many Americans gather at Senor Paco’s Mexican Restaurant, reputedly the only Mexican place on the gulf where the Mexican food doesn’t taste like South Indians cooked it—even though they did.

And yes, I have a t-shirt from Senor Paco’s in my collection. Several, in fact:

Ah, Senor Paco’s where the good times never end, and neither do the karaoke or the margaritas or the funny sombreros that the restaurant hands out for customers to wear. Senor Paco’s is a mecca for all the Americans who still inhabit that part of the old empire. (Because there’s nothing more American than Mexican food.) And they post reviews and pictures and stories about Senor Paco’s on the Internet.

And the new citizens of the empire come to Senor Paco’s as well: the new international technocrats, the new Saudi and European and Indonesian oil brats, They, too, drink the margaritas, eat the nachos, wear the funny sombreros.

I suppose that as long as you can order a carne asade taco on the Persian Gulf or persuade a tipsy Muslim technocrat to wear a sombrero, American influence still lives on in some way.

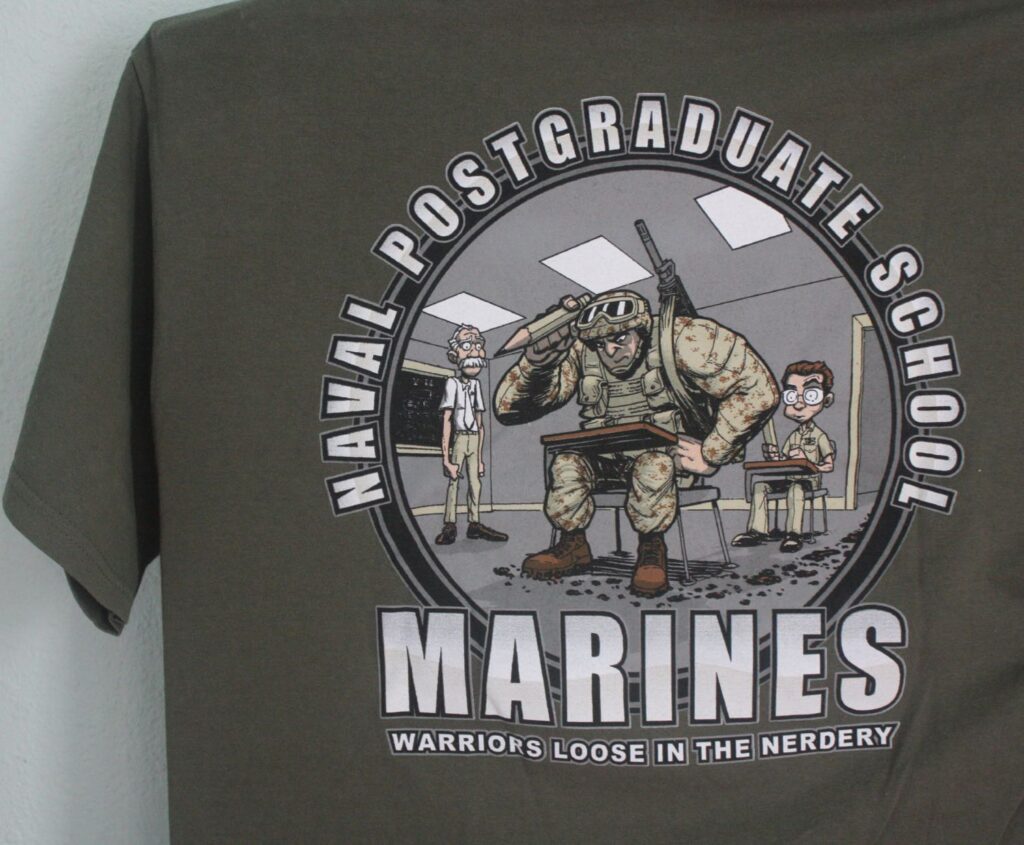

Especially since I have not one, but three Senor Paco’s t-shirts (I sleep in one of them); there’s quite the commute going on between Bahrain and this stretch of California coast — possibly due to the nearby Naval Postgraduate School and the Defense Language Institute, and Bahrain’s role in housing a major U.S. military support facility for Mideast operations.

The DLI puts out its own menacing set of t-shirts of which I have several (“We speak Farsi— so you don’t have to,” “We speak Russian — so you don’t have to,” and on and on.)

But though the empire Americans built still exists, it seems now as if the empire rules us instead of us ruling it. Americans patrol the world; and yet America itself just gets poorer and angrier and more desperate.

Let me pitch you an idea for a new space opera—just like the pulp sci-fi of yore but with a modern sensibility. It takes place in a once-triumphant Earth empire lately gone bad. Earth settled the galaxy in the name of peace, but the multi-stellar corporations gained too much influence; and before too long the Earth empire ruled in the name of greed.

The multi-stellar corporations exploited the natives on a hundred worlds while distracting the humans back on Earth with downloadable holographic movies and electronic pleasure-center stimulators.

Now the multi-stellars have increasingly moved their operations out into the other worlds of the Empire and cut their ties with Earth itself. Earth humans find themselves in hock to their own Empire, which is descending upon them with lawyers and turncoat emperors and public relations experts to foreclose their citizenship rights and turn them into serfs of the New Galactic Order.

A few brave space captains have broken off from the corrupt Galactic Fleet and are rallying the citizens to free themselves from their own empire. Against overwhelming odds.

What do you think? Good idea? Or have you read that one already?