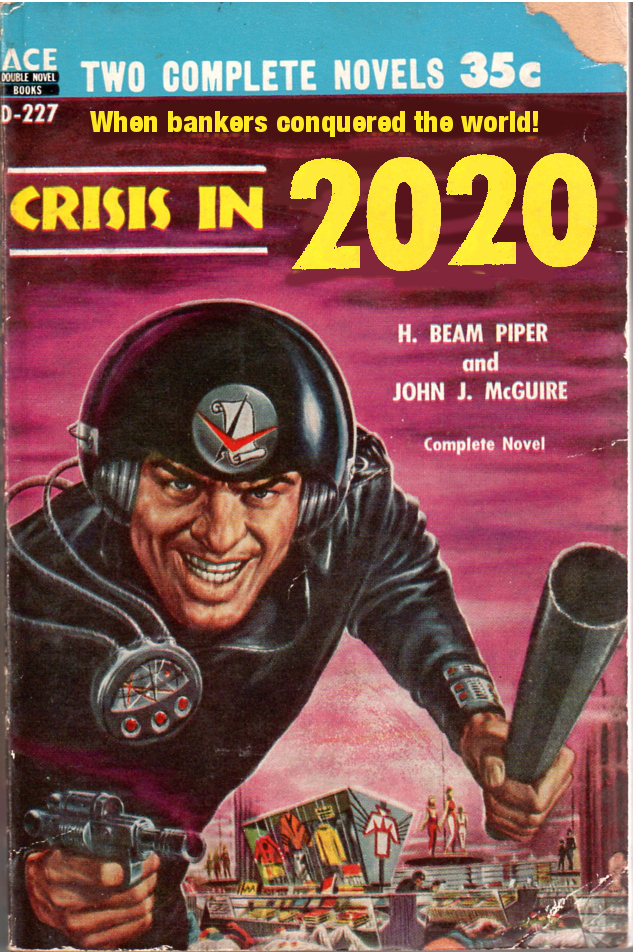

If you’ve read any pulp science fiction and fantasy — and I have, though not for decades — you know all about the Dark Empire.

If you’ve read any pulp science fiction and fantasy — and I have, though not for decades — you know all about the Dark Empire.

The Dark Empire is that distant but mighty star empire which swoops down on the peaceful settlers of the planet Zipperdork 3 and suborns them to its plans for galaxy-wide conquest.

Or, in heroic fantasies, the Dark Empire inhabits the chaotic land of Dystopia from which it dispatches hordes of spell-flinging calvary to overrun the peaceful kingdom of Dragonsbane and enslave the heir to the throne inside a tower well secured by charms, demons, and bureaucrats.

The variations are endless. What’s inevitable, though it may take several thousand pages, is that a few plucky starship captains will discover the lost super weapons of the ancient Vleen race and char-broil the empire’s neutronium-plated space fleet.

Or, a ragged slave boy will find the magic sword Phallusia in the lost city of Oxnard and fulfill an ancient prophecy by slicing the Dark Empire’s calvary into flank steaks. And acquire the throne of Dragonsbane in the meantime, plus an interesting scar.

Whatever. If you’ve seen a Star Wars movie, or a Lord of the Rings flick, you’ve pretty much got it.

The thing is, the thing that really bothers me, is that nobody ever fills in the back-story for the Dark Empire.

Sure, the Dark Empire can field fleets of star destroyers and hordes of well-equipped warriors. But who builds the starships? Who joins the army? Where did these people go to school? Who raises the food? You can’t conquer the galaxy, or even the trackless wastes of Dragsonbane, without a complete civilization to support you.

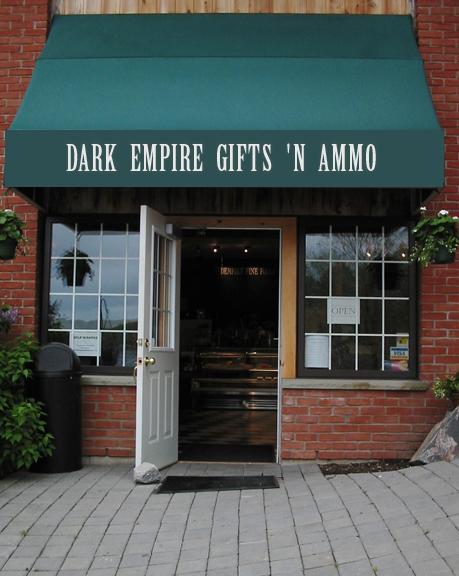

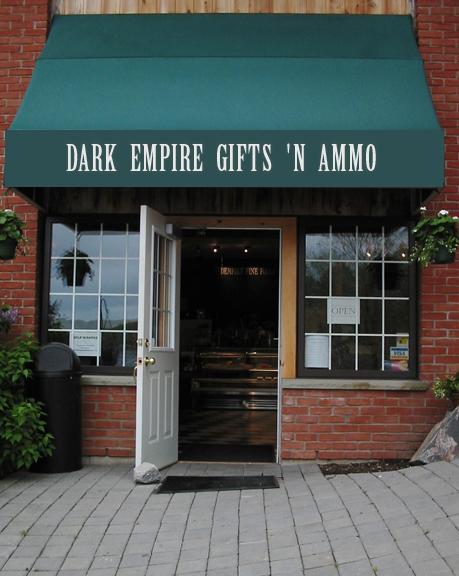

So, somewhere there must be a Dark Empire homeland. And no doubt you will find there the Dark Empire Missiles and Space Corporation, the First Bank of the Dark Empire, the Dark Empire Unified School District, Dark Empire Mall, and the Dark Empire Parks and Recreation Ministry. There are festivals and patriotic holidays, a Dark Empire Football League, and certified public accountants.

So, somewhere there must be a Dark Empire homeland. And no doubt you will find there the Dark Empire Missiles and Space Corporation, the First Bank of the Dark Empire, the Dark Empire Unified School District, Dark Empire Mall, and the Dark Empire Parks and Recreation Ministry. There are festivals and patriotic holidays, a Dark Empire Football League, and certified public accountants.

And millions of people who lead normal lives, go to work every day, raise children, and wave the flag. It doesn’t take much to keep them in line; the Dark Emperor just need to use the right words:

The emperor doesn’t “invade,” he “defends the Dark Empire’s strategic interests.” He doesn’t “blackmail” the tiny Kingdom of Twee into giving him their gold and treasure, he “welcomes them into the galactic economy.” It goes without saying that the Dark Empire troops never rape, torture, or pillage. But if someone does say it, the Dark Emperor talks solemnly about “human rights violations,” and finds a low-ranking scapegoat.

The emperor doesn’t “invade,” he “defends the Dark Empire’s strategic interests.” He doesn’t “blackmail” the tiny Kingdom of Twee into giving him their gold and treasure, he “welcomes them into the galactic economy.” It goes without saying that the Dark Empire troops never rape, torture, or pillage. But if someone does say it, the Dark Emperor talks solemnly about “human rights violations,” and finds a low-ranking scapegoat.

And so the Dark Empire’s citizens are reassured and go back to sleep, and to their jobs making Nova Bombs or poisoned daggers for the Dark Empire’s fighting men.

And that’s why, from now on, I will refer to the United States’ armed Predator and Reaper drones as “flying robot assassins.” Which is, up till now, a term used only in the Middle East.

And that’s understandable. The news from Yemen this past week was all about a dozen or more U.S. drone attacks; each one sought out and killed specific people who were terrorist suspects. Plus a fair number of innocent bystanders, but only a few independent Yemeni news sources mention that.

So what’s the different between a drone and a flying robot assassin? Not much; they’re both robots, they both fly, and they both seek out and kill particular people who may or may not be engaged in combat. Which is the definition of assassination.

Just, the word drone is neutral, safe, unexciting. If President Obama talks casually about the need for flying robot assassins to protect U.S. interests abroad — questions will be asked. Those words are dangerous. People might begin to wonder why the world’s leading democracy, its beacon of freedom, needs an ever-growing force of flying robot assassins.

The famous cynic George Orwell wrote that a nation’s gone completely corrupt when nobody dares call anything by its real name. Bribes become “campaign contributions.” Domestic spying is called “anti-terrorist activity.” And flying robot assassins are just, you know, unmanned aerial vehicles. Drones.

Inside the Armed Services, of course, they don’t mince words. The armed drones have model names like “Predator” and “Reaper,” and the military glories in the bloody imagery. Here’s a t-shirt that the Air Force gives to a particular flight of recruits upon passing basic training (321st Training Squadron, Flight 532,”The Predators,” out of Lackland AFB in San Antonio):

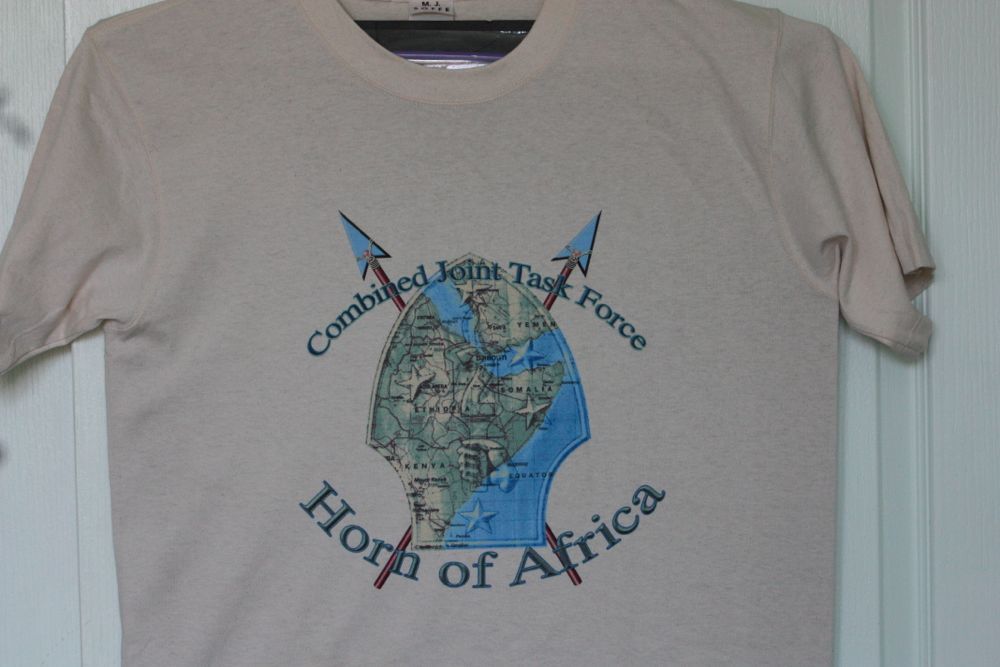

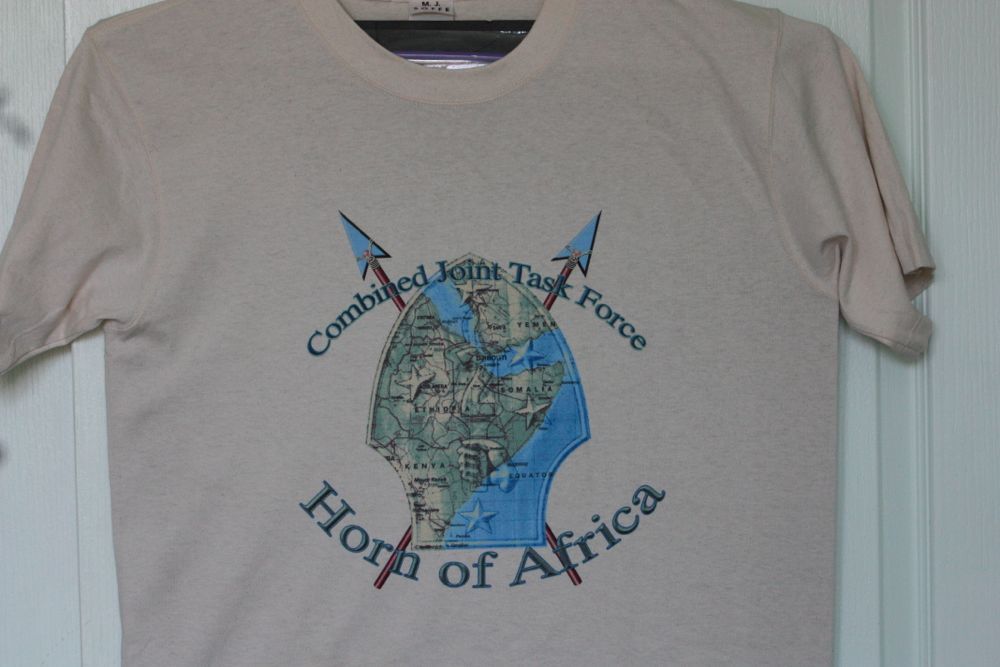

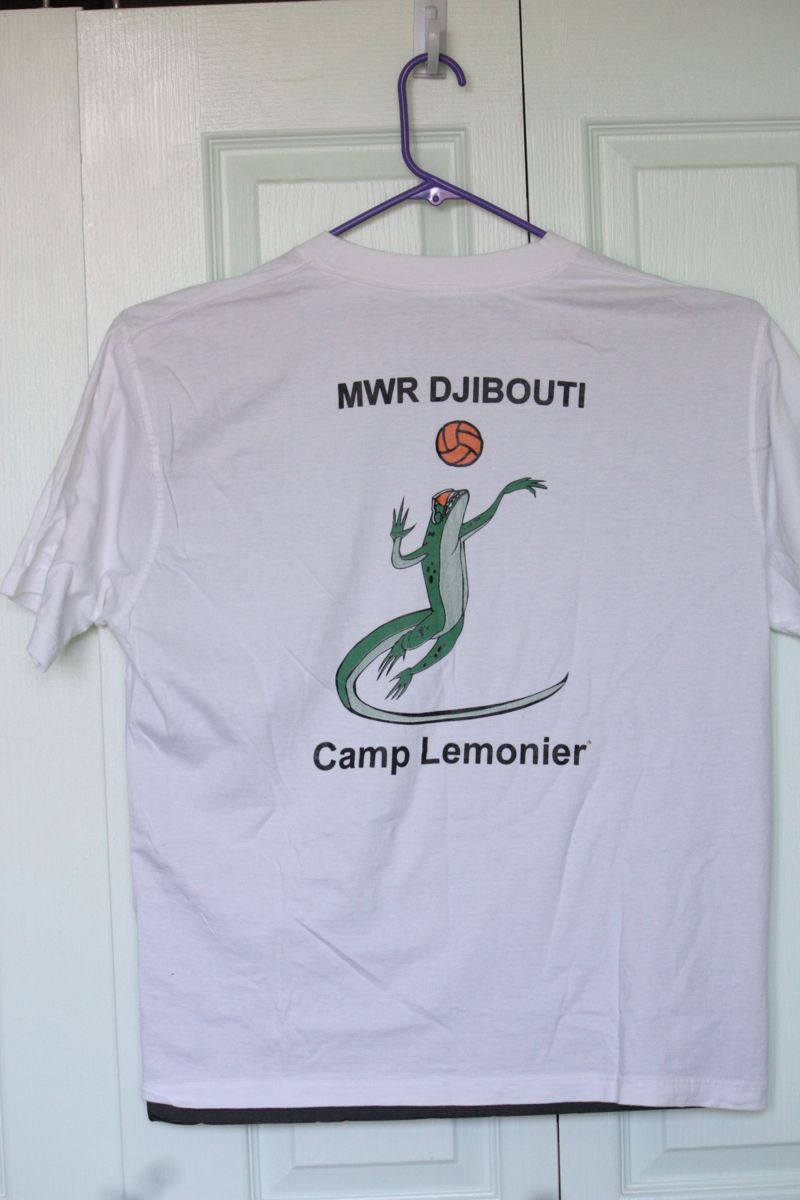

For those of you who don’t know me well: I collect t-shirts of significance that show up in local thrift shops. Whatever America does in the world, wherever, it leaves behind a trail of t-shirts. Here is a tee that is all about flying robot assassins, even if it’s not so obvious.

The Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa is the future of anti-terrorism in the Middle East. In large part, it’s also a grim base and airfield called Camp Lemonnier in the baking-hot desert nation of Djibouti, on the Gulf of Aden. Djibouti’s natural resources consist of dirt, rock, trash, lizards, camels, and a free trade zone. It is perhaps the poorest nation you’ve never heard of. Desperately poor.

And thus Djibouti was happy to let the U.S. do anything it wanted with Camp Lemonnier, a derelict French Foreign Legion base. Conveniently located near Yemen, Somalia and the underbelly of the Middle East.

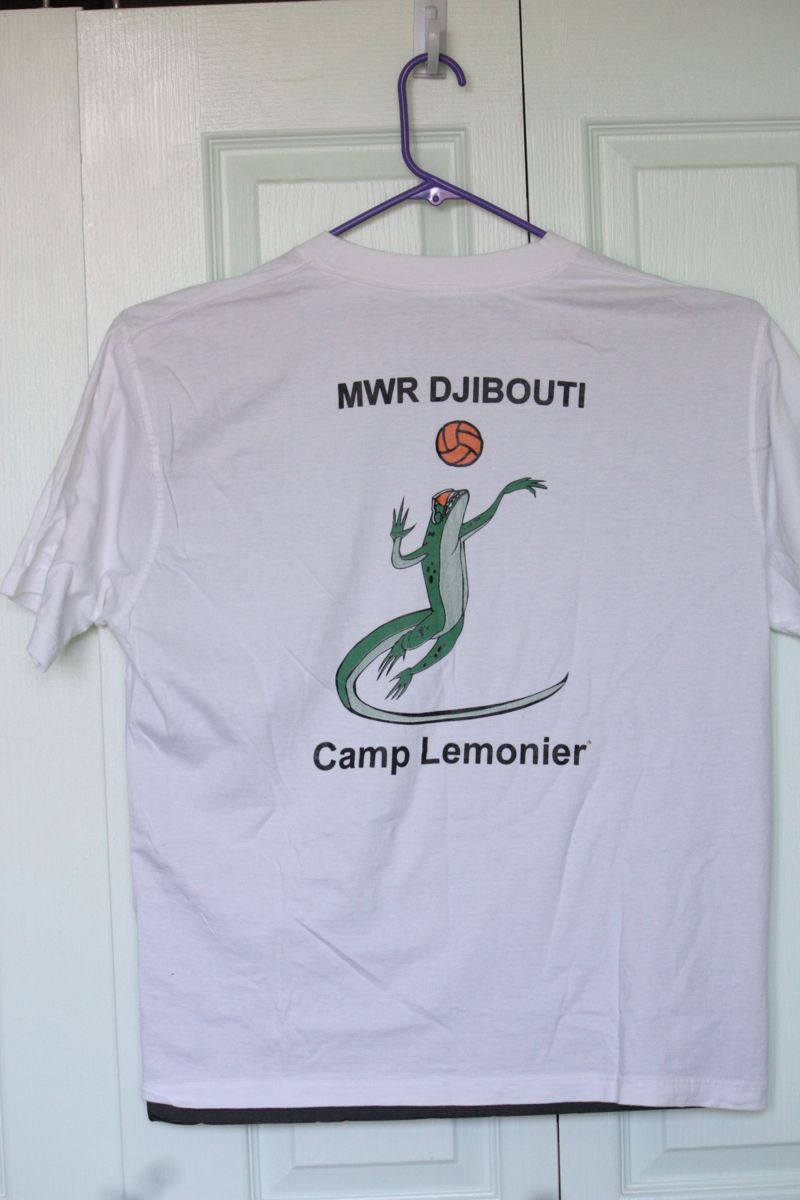

Camp Lemonnier is a pit: hot, dry, dusty, drab, desolate. Mind you, it’s a pit with a giant weight room and fitness center. And the Bob Hope Chow Hall where, on Thanksgiving, low-paid Filipino contract workers dress up as Indians and Pilgrims to serve turkey, steak, and crab to beefy men and women in green uniforms.

There’s even a Thanksgiving parade, though I don’t think the real Mayflower ever flew the skull and crossbones.

And the Morale, Welfare and Recreation (MWR) office does what it can, like arranging for traveling rock bands from Northern Iowa (“The Blue Island Tribe”) to play a Christmas Eve gig on the big stage, or putting on volleyball tournaments with free t-shirts – one of which ended up in Santa Cruz. I wonder whether Camp Lemonnier has on-base silk-screen capability or had to have the tees flown in. And there’s a coffee house, the Green Bean, with two locations and WiFi.

Camp Lemonnier is also home to 400 to 800 Navy Seals, Army Delta Force special ops troops, and intelligence agents; five F-15 fighter-bombers; several spy planes; and a goodly flock of flying robot assassins. I can find very few pictures of all that, though MWR let the Blue Island Tribe play with grenade launchers and hang out in the spy planes.

So when anyone judged to be a terrorist or sympathizer dies in Yemen or Somalia or anywhere nearby, their cause of death likely flew in from Camp Lemmonier. From a flying robot assassin, or from real live assassins working beyond the bounds of law and constitution as we know it. But who believe, or at least are told, that they’re defending their country from terrorism. And they’re going to keep doing it for years to come; Washington is spending over a billion to make Camp Lemonnier a permanent base. The war on terrorism will never end.

And there’s the ghost of George Orwell in the back of the room, waving a finger in the air: if we can’t call things by their real name anymore, what’s the real name of terrorism?

I hate to tell you: it’s “resistance.” Resistance by people who aren’t really awfully wonderful in any way, shape or form. Resistance led, often, by fanatical, hateful religious zealots. But zealots with one valid point: that U.S. and the West have been trampling the region’s sovereignty for the last 70 years in the name of oil and big corporate interests. (Name one other reason we’d care so much about the Middle East.) And they’d like us to leave.

They’ve chosen terror as their weapon, because it’s what you can use when the other guy has all the guns and bombs and planes and body armor. And when your anger and hatred, perhaps, has grown past the edge of madness. So you try to break the will of the enemy nation, because you can’t break their troops. Ramming airliners into the World Trade Center is one way to do that. Especially when some people interpret “World Trade” as a code name for the Dark Empire.

The wiggly thing about a Dark Empire is that it never looks dark from the inside. It can’t, or its own people would begin to disavow it. So the gentle control words are used: “defense against terrorism,” “support our troops,” “spreading democracy.”

And since it’s actually doing none of those things in recent years, from the outside our Dark Empire just seems darker and darker. As it fights not the War on Terror, but the War on Resistance: resistance to a world-girdling oligarchy of power, money, and greed that is based right here in America.

Might be a hell of a pulp novel in it, eventually. Though maybe not one you’d want to be a character in.

As if you had a choice.